THE SCIENCE OF GROUNDWATER

The Hydrologic Cycle - The Foundation of Groundwater

To understand groundwater, we must first explore the natural cycle that drives it - the hydrologic cycle.

The hydrologic cycle continuously moves water through Earth’s systems.

The key processes involve are:

Precipitation

Evaporation

Runoff

Infiltration

Plant uptake

Transpiration

Groundwater begins when water infiltrates from the surface into the ground.

Once water reaches the ground, it begins the process of becoming groundwater through infiltration and percolation.

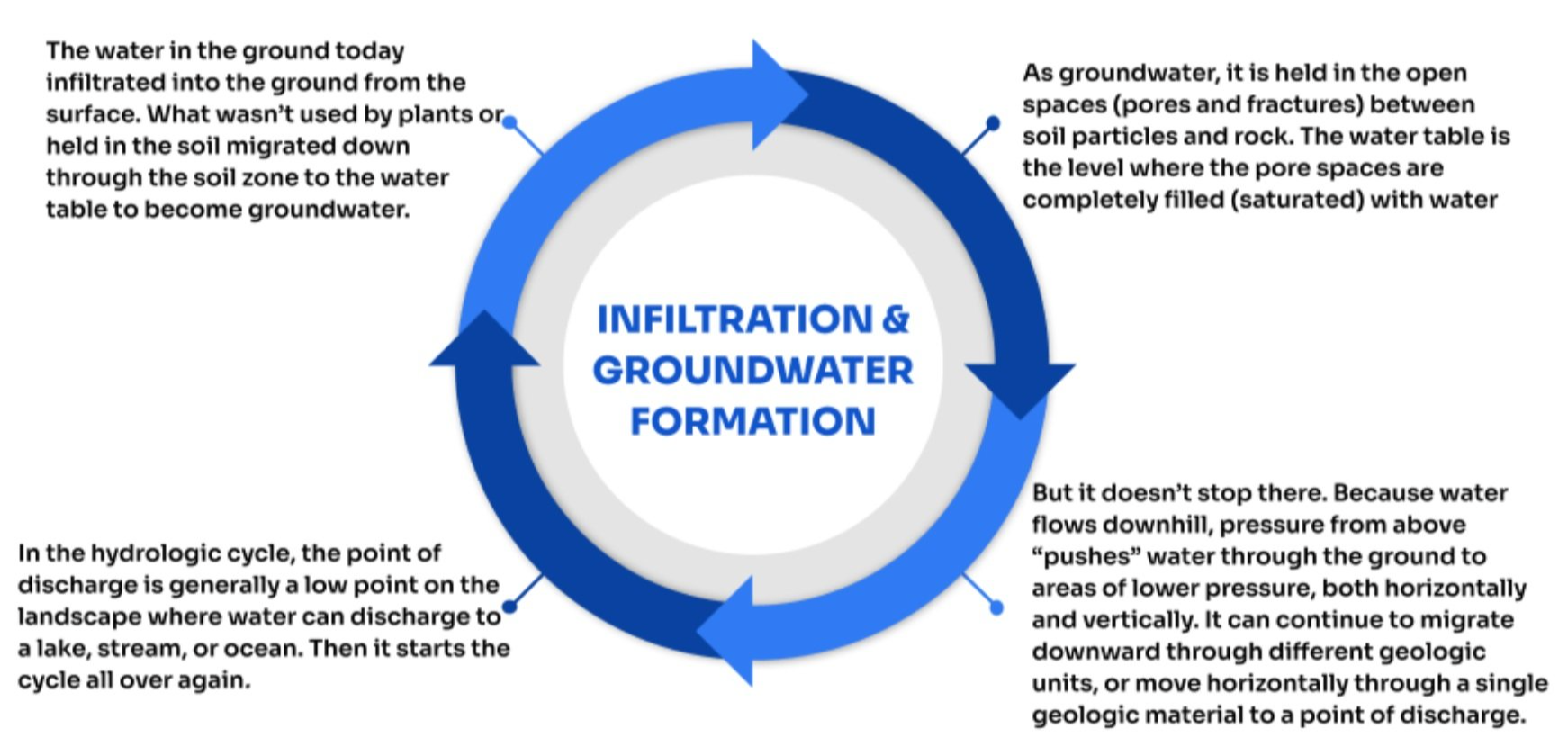

Infiltration & Groundwater Formation

Groundwater doesn’t stay still—it moves slowly through Earth’s materials, shaping where and how it resurfaces.

Water flows downhill and from areas of higher pressure to lower pressure.

It may move vertically through different layers or horizontally across a single geologic formation.

Groundwater eventually reaches discharge points like rivers, lakes, or oceans.

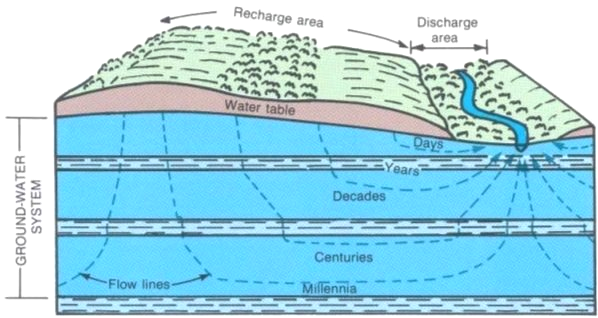

Groundwater movement is a slow process, so slow that some water can remain underground for centuries.

What is an aquifer and why it is important?

Aquifers are underground formations that collect and store groundwater, critical for human use.

Aquifers hold water in porous soil materials or fractures in bedrock.

Wells pump water directly from these underground storage zones.

Aquifers vary in depth and composition, affecting water access and quality.

Aquifers are critical sources of groundwater, supplying wells with usable water through storage and flow.

How does permeability control groundwater flow?

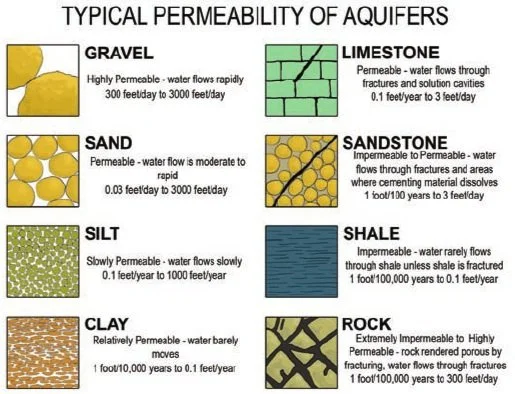

Permeability is what makes an aquifer productive - it allows water to move freely to wells.

Permeability = ease of water movement through a material.

High: sand/gravel → fast water flow

Low: clay/silt → restricted movement

High porosity ≠ high permeability (e.g., clay has high porosity, but water moves slowly).

Water must flow freely to well to maintain pumping rate.

Low permeability = low productivity wells.